The Complete Social Anxiety Treatment Guide: A Science-Based Roadmap

This article contains recommendations for products and services that we genuinely endorse for individuals with social anxiety. If you purchase products or services through our links, you may receive a significant discount and we will receive a commission.

Embarking on the journey to overcome social anxiety disorder can feel like an overwhelming feat. Surprisingly, even though effective treatments exist, research shows that only one in five individuals affected by social anxiety seek professional help for their condition (Grant et al., 2005).

Often, a paradox lies within the very nature of social anxiety. While individuals yearn for help and support to alleviate their distress, this desire can be overshadowed by fears of potential judgment and negative evaluation from healthcare providers.

Moreover, many also harbor concerns about the judgment and reactions from their loved ones and acquaintances, further complicating their willingness to seek assistance.

This internal conflict creates a barrier that hinders many from seeking the treatment they genuinely deserve. As a result, their distress persists, and opportunities for personal growth become limited.

Furthermore, financial implications, geographical limitations, and the scarcity of professionals specializing in social anxiety disorder can further complicate the path to accessing treatment (Mechanic, 2007; Olfson et al., 2000).

However, it’s essential to remember that these barriers can be overcome, and there are effective strategies that can significantly improve social anxiety symptoms and enhance overall well-being.

If you find yourself wrestling with social anxiety and longing for potent strategies to conquer this challenge, take solace in the fact that you are not alone.

This carefully curated guide is specifically tailored to provide invaluable insights and resources, empowering individuals with social anxiety to discover the support they need through proactive measures.

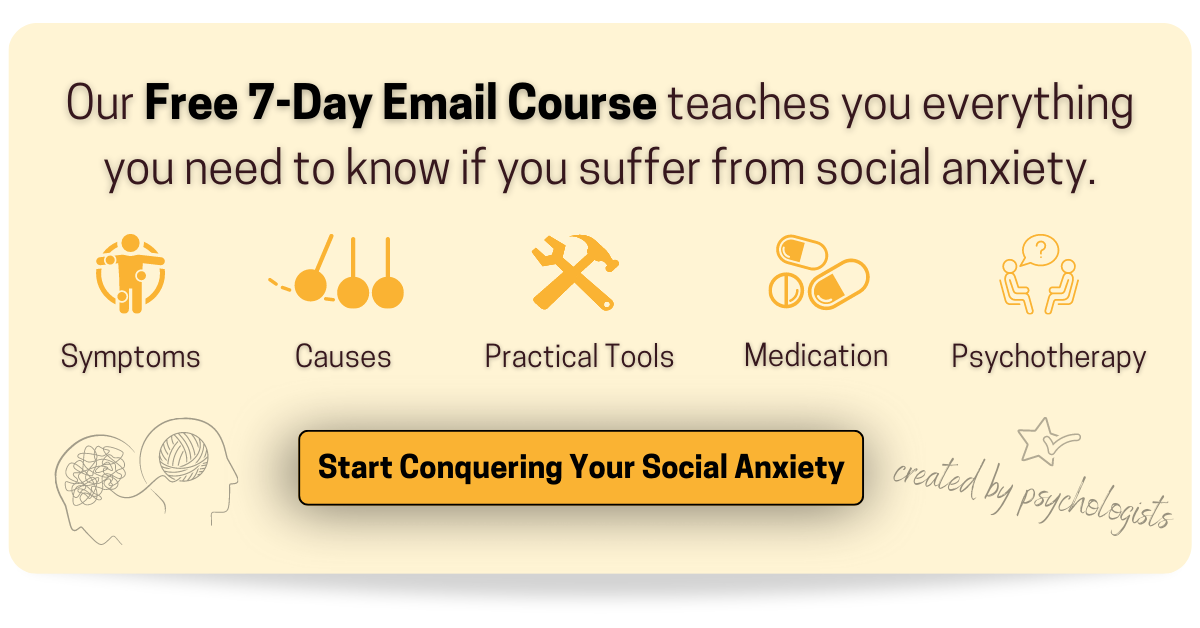

We will present four crucial strategies that play a pivotal role in effectively treating and conquering social anxiety. Allow us to provide you with a glimpse of these powerful techniques, each of which will be elaborated upon in detail as you delve deeper into the content.

(1) Psychotherapy

At the core of social anxiety treatment lies psychotherapy, a collaborative and supportive therapeutic approach.

Evidence-based therapies such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, psychodynamic therapy, interpersonal therapy, acceptance & commitment therapy, metacognitive therapy, mindfulness- and compassion-based therapy and group interventions all offer valuable insights and strategies to address the underlying causes of social anxiety, challenge negative thought patterns, and develop effective coping mechanisms.

We will introduce each of these different therapeutic approaches, all of which have proven to effectively reduce social anxiety in scientific studies, aiming to provide you with a basic understanding of each, so you can make informed decisions regarding your therapeutic journey.

Overall, psychotherapy is the cornerstone of social anxiety treatment, offering a holistic, evidence-based approach that fosters understanding, skill development, and lasting transformation, enabling individuals to overcome their social anxiety and lead fulfilling social lives.

(2) Medication

In some cases, medication may be prescribed to complement psychotherapy and alleviate social anxiety symptoms.

Medications such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), benzodiazepines, beta-blockers, monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), and reversible inhibitors of monoamine oxidase A (RIMAs) can help manage anxiety levels and provide additional support on your journey.

Furthermore, we will explore a natural alternative called CBD (Cannabidiol), which has shown promise in scientific studies for managing social anxiety. CBD offers potential benefits with fewer side effects compared to traditional medications.

Consulting with a qualified healthcare professional will help determine the appropriateness and potential benefits of medication for your specific needs.

(3) Self-Help Techniques & Lifestyle Changes

Beyond therapy and medication, self-help techniques and lifestyle changes play a crucial role in managing social anxiety. They empower you to take an active role in your treatment and promote overall well-being.

We will explore various self-help techniques and lifestyle changes that can effectively support you in overcoming social anxiety. These include establishing a foundation for well-being, building self-awareness, acquiring coping strategies, and improving social skills.

These strategies will be discussed in detail, providing you with practical insights and guidance to integrate them into your daily life.

(4) Building a Support Network

The importance of building a support network is often undervalued and underrated in the journey of overcoming social anxiety.

Having a supportive network of individuals with whom you can openly share your experiences and feelings is crucial, as they can serve as a reliable source of support and comfort during temporary setbacks, which are indeed a normal part of the recovery process from social anxiety.

We’ll explore the benefits of local support groups, as well as online forums and communities where you can connect with individuals who share similar experiences and challenges. Additionally, we emphasize the power of fostering healthy relationships and actively engaging in social activities.

By nurturing relationships with compassionate and empathetic individuals, you create an emotional safety net that provides understanding, acceptance, and encouragement.

A strong support network cannot only be the difference between feeling isolated and finding a sense of belonging, understanding, and validation, but also play a vital role in ensuring that you stay socially active, engaged, and continuously practice your social skills.

By combining these various treatment modalities, you can create a comprehensive approach to managing social anxiety and reclaim control over your life.

Throughout this guide, we will explore each aspect in depth, providing practical tips, valuable resources, and insights to empower you on your path to overcoming social anxiety.

Given the comprehensive coverage presented in this article, we highly recommend bookmarking it in case you are unable to complete reading it in a single session. This way, you can easily come back to it at a later point.

Let’s get started.

A. Understanding Social Anxiety: A Brief Overview

Social anxiety disorder, also known as social phobia, is a common mental health condition that affects millions of individuals worldwide.

A recent extensive study conducted across multiple cultures revealed that approximately one in three individuals between the ages of 16 and 29 meet the diagnostic criteria for this condition (Jefferies & Ungar, 2020).

But social phobia is not limited to any specific age group; rather, it affects individuals across the lifespan, demonstrating its prevalence among people of all ages.

Social anxiety disorder is characterized by an intense and persistent fear of social situations, often accompanied by feelings of self-consciousness, apprehension, and the fear of being negatively judged or evaluated by others (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

The symptoms of social anxiety can manifest in various ways, including:

Physical symptoms: Rapid heartbeat, sweating, trembling, shortness of breath, nausea, and dizziness.

Cognitive symptoms: Excessive worry, negative self-talk, fear of embarrassing oneself, and difficulty concentrating.

Behavioral symptoms: Avoidance of social situations, reluctance to speak up or participate, and a strong desire to blend into the background.

It is important to note that social anxiety exists on a spectrum, and its severity can vary greatly among individuals.

While some individuals may experience mild discomfort in specific social situations, others may feel incapacitated by their fear, making it challenging to engage in even routine social interactions.

The causes of social anxiety are complex and can be influenced by a combination of genetic, biological, psychological, and environmental factors (Rose & Tadi, 2021).

Traumatic experiences, negative social interactions, a family history of anxiety, and an overactive fear response system in the brain can all contribute to the development of social anxiety disorder.

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the various causes and factors that can contribute to the development of social anxiety, we invite you to explore our dedicated article on this topic by clicking here.

The impact of social anxiety on daily life can be profound. It can hinder educational and career opportunities, strain personal relationships, and lead to a diminished quality of life (Alomari et al., 2022).

Individuals with social anxiety may feel isolated, misunderstood, and may struggle to fulfill their potential due to the fear and avoidance of social situations.

If you’re curious to explore the profound impact that living with social phobia can have on various aspects of life, we encourage you to click here to delve into our in-depth article on the 10 most serious consequences of social phobia.

However, it is crucial to remember that social anxiety is a treatable condition. With the right support, strategies, and professional guidance, individuals can overcome the limitations of social anxiety and regain control over their lives.

Throughout the rest of this article, we will have an in-depth look at how exactly this can be achieved.

B. Psychotherapy: The Pillar of Social Anxiety Treatment

Psychotherapy stands as a fundamental pillar in treating social anxiety, providing you with understanding, healing, and growth. Through therapy, you can unravel the layers of your social anxiety, uncover underlying causes, and develop effective strategies to reduce and overcome it.

Psychotherapy, also known as talk therapy or counseling, offers a safe and confidential space to examine your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors in the context of social anxiety.

Collaborating with a skilled therapist, you’ll navigate evidence-based techniques tailored to your needs, illuminating the path forward and freeing you from social anxiety’s grip.

In order to offer you a thorough understanding of the available options, we explore various types of psychotherapy commonly utilized for social anxiety.

These include Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy, Psychodynamic Therapy, Interpersonal Therapy, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, Metacognitive Therapy, Mindfulness- and Compassion-Based Therapy, as well as Group Therapy.

Each approach offers unique strengths and approaches to unravel the complexities of social anxiety, build resilience, and foster meaningful change.

In addition to alleviating social anxiety symptoms, psychotherapy also nurtures self-acceptance and personal growth (Chui et al., 2021).

Cultivating self-awareness, self-compassion, and coping skills enables you to flourish beyond social anxiety’s confines, embracing fulfilling relationships, self-expression, and expanded possibilities in life.

Let’s get started and equip you with the knowledge to make informed decisions about your therapeutic journey.

The Basics of Psychotherapy

When considering psychotherapy as a treatment option for social anxiety, it’s helpful to have a general understanding of what to expect. Here are some key aspects to consider.

Cost and Health Insurance Coverage

The cost of psychotherapy can vary depending on factors such as location, therapist credentials, and the specific type of therapy.

In countries like the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, the typical range for psychotherapy sessions is between $80 and $250 per session, but this can vary significantly.

It’s important to check with your health insurance provider to determine if mental health services, including psychotherapy, are covered.

Many insurance plans offer coverage for therapy, but it’s crucial to understand any copays, deductibles, or limitations.

Additionally, some therapists offer sliding-scale fees or reduced rates based on income, making therapy more accessible to individuals with financial constraints. It is worth inquiring about these options when seeking psychotherapy.

Dosage and Duration

The frequency and duration of psychotherapy sessions can vary depending on individual needs and treatment goals.

Initially, sessions may be scheduled on a weekly basis, lasting around 50 minutes each. As progress is made, sessions might become less frequent, transitioning to biweekly or monthly meetings.

The overall duration of therapy can vary, ranging from several weeks to months or even longer, depending on the complexity of the social anxiety and individual progress.

It’s important to note that the length or duration of therapy can also be influenced by the type of therapy chosen.

For example, psychodynamic therapy, which focuses on exploring unconscious patterns and childhood experiences, typically extends over a longer period, often spanning several months and sometimes even years.

In contrast, cognitive-behavioral therapy, known for its structured and goal-oriented approach, may be more time-limited and range from several weeks to several months.

In general, the duration of psychotherapeutic interventions for social anxiety varies, but it commonly involves a course of several sessions over a period of weeks or months to effectively address the condition.

Finding a Good Therapist

Finding a qualified and compatible therapist is crucial for a successful therapeutic experience. Start by seeking recommendations from trusted sources, such as your primary care physician, friends, or family members.

You can also utilize online directories and mental health resources, which provide a wealth of information to help you find therapists specializing in anxiety disorders and different therapeutic approaches.

When choosing a therapist, it is crucial to consider important factors such as their credentials, experience, and their specific approach to treating social anxiety.

It’s worth noting that there are various therapeutic modalities beyond cognitive-behavioral approaches that have shown effectiveness in addressing social anxiety (which we will discuss shortly). It is essential to select an approach that resonates with you and makes you feel comfortable.

It is also crucial to feel at ease and establish a good rapport with your therapist, as the therapeutic relationship plays a vital role in the effectiveness of treatment.

In fact, the so-called therapeutic alliance is considered one of the most important preconditions for effective treatment (Tschuschke et al., 2020; Weck et al., 2015).

Don’t hesitate to schedule initial consultations with potential therapists to assess the therapeutic fit and determine if they are the right match for your needs and preferences.

Trusting your instincts and finding a therapist with whom you feel understood and supported is key to a positive therapeutic experience.

In-person vs. Online Therapy

With advancements in technology, therapy is no longer limited to in-person sessions. Online therapy, also known as teletherapy or telehealth, offers the convenience of accessing therapy remotely through video calls or secure messaging platforms.

It can be an accessible option for individuals who may find it challenging to attend in-person sessions and has shown to effectively reduce social anxiety symptoms, similar to in-person therapy (Kampmann et al., 2016).

For individuals with social anxiety who harbor significant reluctance towards seeking in-person treatment, messaging or chat therapy presents an invaluable option. It effectively lowers the barrier to initiate therapy, providing them with an accessible means to seek help and support.

Online therapy provides flexibility in scheduling, eliminates geographical barriers, and may offer a greater selection of therapists to choose from.

However, it is vital to ensure that the therapist is licensed and adheres to ethical guidelines. Furthermore, it is essential to prioritize the security and privacy of your personal data when selecting an online therapy platform.

Verify that the chosen platform employs robust security measures to safeguard your confidential information throughout the therapeutic process.

After meticulous evaluation of online therapy providers, we confidently endorse online-therapy.com as the premier choice for English-speaking individuals seeking support with social anxiety.

Their personalized 45-minute live sessions in video, voice, or text format, unlimited messaging, and comprehensive 8-section CBT program make them an exceptional choice.

Plans start at just $40 per week. You can use the following link to sign up, which will grant you a 20% discount for your first month of therapy.

Once again, the specifics of psychotherapy, including costs, insurance coverage, and therapy options, can vary depending on your location and individual circumstances.

It’s recommended to consult with mental health professionals, insurance providers, and trusted sources to gather accurate and personalized information for your unique situation.

Next, we will delve into specific types of psychotherapy frequently employed in the treatment of social anxiety. Let’s explore their distinctive approaches and effectiveness in addressing social anxiety!

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy stands as the most widely utilized therapeutic approach for social anxiety disorder, supported by an extensive body of scientific research affirming its effectiveness.

Numerous meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated the efficacy of CBT in addressing and managing symptoms associated with social anxiety with large effect sizes (e.g., Acarturk et al., 2009; Barkowski et al., 2016; Mayo-Wilson et al., 2014).

CBT operates on the principle that our thoughts, beliefs, and behaviors influence our emotions.

By identifying and challenging negative thoughts related to social situations, you can transform your thinking patterns and develop healthier, more adaptive responses.

One key aspect of CBT for social anxiety is examining and restructuring cognitive distortions.

These distortions are automatic and irrational thoughts that contribute to anxiety, such as catastrophizing (exaggerating negative outcomes), mind reading (assuming others have negative perceptions), or overgeneralizing (drawing sweeping negative conclusions based on limited experiences).

Through guided exploration with a trained therapist, you can learn to recognize these distortions and replace them with more balanced and realistic thoughts.

This process helps to alleviate anxiety and promotes a shift towards more positive self-perceptions and social interactions.

Behavioral techniques also play a significant role in CBT for social anxiety.

Exposure therapy, a central component of CBT, involves gradually and systematically facing feared social situations in a supportive and controlled manner.

By confronting anxiety-provoking situations, you can learn that your feared outcomes are often unlikely to occur, and your anxiety diminishes over time.

Additional behavioral strategies may include social skills training, assertiveness training, and relaxation techniques to manage physiological symptoms associated with anxiety.

It is important to note that the duration of CBT for social anxiety can vary depending on individual needs and progress.

Typically, treatment consists of several weeks or months of regular sessions, with an average of 12 to 16 sessions. However, the exact length and frequency of therapy should be discussed with your therapist.

For a comprehensive understanding of CBT for social anxiety, including numerous practical worksheets, we highly recommend the CBT workbook for social anxiety (available for purchase here).

It is authored by three leading experts in social anxiety and CBT and it can be effectively used in therapy with a professional or as a standalone tool for self-improvement.

If you’re interested in delving deeper into CBT for social anxiety and explore this approach in-depth, you can click here to read our introductory guide to CBT for social anxiety. It offers comprehensive insights and practical guidance for incorporating CBT into your journey of overcoming social anxiety.

As all psychotherapeutic approaches for social anxiety, CBT is a collaborative process between you and your therapist.

By actively engaging in therapy and practicing the techniques learned, you can gain valuable skills to challenge negative thinking patterns, manage anxiety, and cultivate more fulfilling social interactions.

Psychodynamic Therapy (PDT)

In the realm of social anxiety treatment, psychodynamic therapy stands as a profound approach that delves into the underlying roots and unconscious processes influencing your struggles.

This therapeutic modality, often also referred to as insight-oriented therapy, offers unique insights by examining your past experiences, relationships, and emotions, with the goal of bringing about lasting change and healing.

PDT recognizes that social anxiety often originates from unresolved conflicts, early childhood experiences, or unconscious patterns of thinking and behaving.

By unraveling these hidden dynamics, a common outcome is a reduction in symptoms associated with social anxiety.

Contrary to a widespread belief that psychodynamic therapy lacks evidence to support its effectiveness, there is an increasing body of literature that substantiates its efficacy as a therapeutic intervention, including in the treatment of social anxiety (e.g., meta-analysis by Zhang et al., 2022).

Recent studies have shed light on the positive outcomes achieved through psychodynamic therapy, providing evidence of its value in addressing the complexities of social anxiety and promoting meaningful change (Keefe et al., 2014; Bandelow et al., 2015).

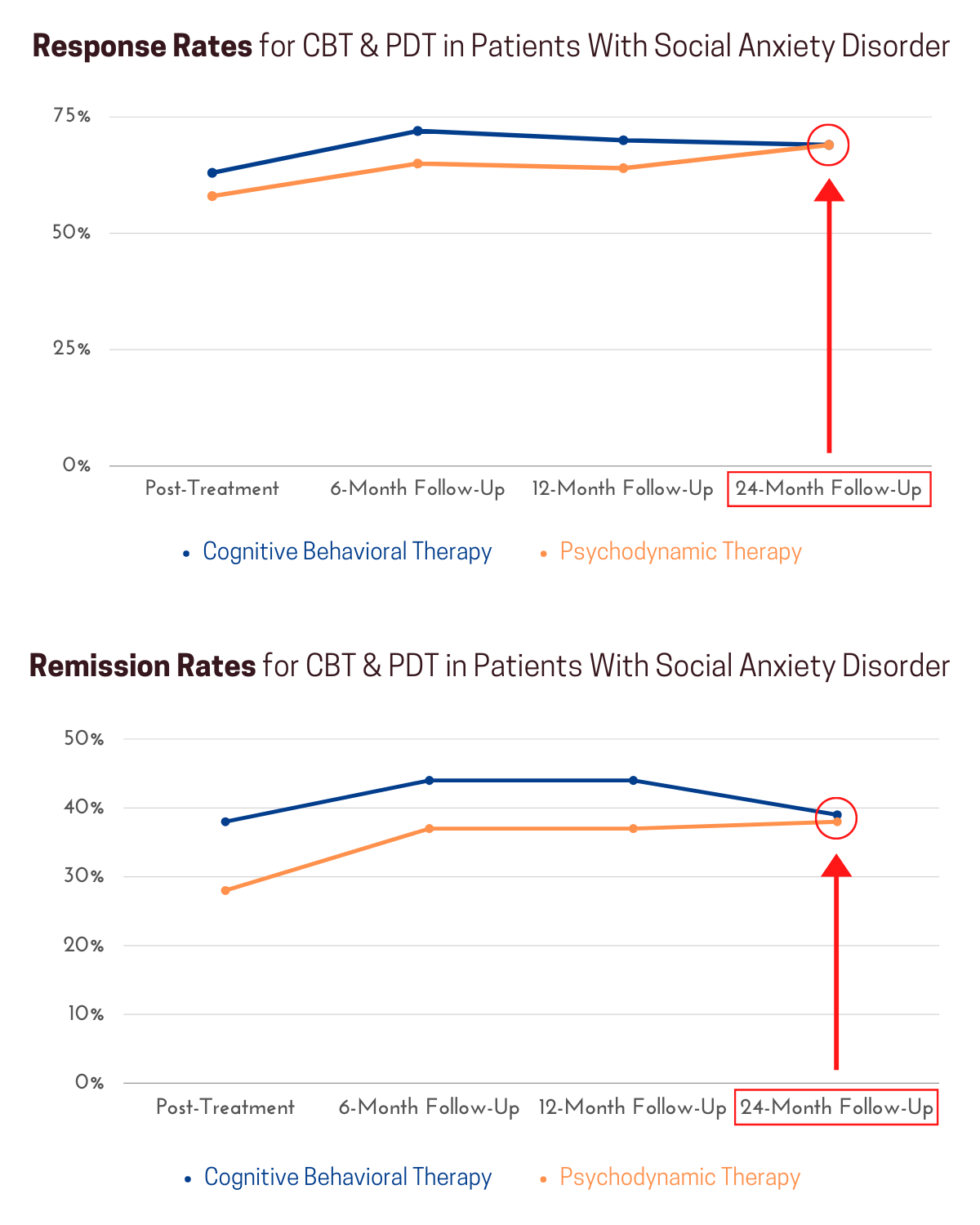

A comprehensive study conducted by a group of researchers (Leichsenring et al., 2014) directly compared the effectiveness of CBT and PDT for social anxiety. Notably, the study examined the long-term effects of these treatments.

The findings, as depicted in the following graphic, demonstrate that both therapies yielded comparable effectiveness, particularly in the long run.

As evident from these research findings, PDT has been established as a valid and effective treatment approach for social anxiety.

It is important not to be swayed by unfounded criticism that lacks scientific grounding. Considering the evidence-based support for PTD, it is worthwhile to explore this therapeutic approach with an open mind and make informed decisions based on scientific knowledge.

In psychodynamic therapy, a collaborative and trusting therapeutic relationship becomes the foundation for your journey of exploration and self-discovery.

Together with your therapist, you delve into the thoughts, feelings, and memories that contribute to your social anxiety, shedding light on unconscious processes that may have hindered your progress.

The therapeutic relationship itself holds great significance in psychodynamic therapy, providing a safe space for you to openly express your thoughts and emotions.

Through this process, you can identify recurring patterns, defense mechanisms, and unresolved conflicts that contribute to your social anxiety symptoms.

By gaining awareness of these unconscious influences, you develop insights into how they shape your perceptions, beliefs, and behaviors in social situations.

This heightened self-awareness creates an opportunity to challenge and modify these patterns, paving the way for more fulfilling and authentic social interactions.

Psychodynamic therapy is often long-term and intensive, as it aims to create lasting and profound change by exploring the depths of your psyche.

Weekly sessions provide consistent support and guidance throughout the therapeutic process, with the duration of therapy ranging from several months to years based on your unique needs and goals.

However, in addition to long-term and intensive psychodynamic therapy, there are also effective short-term interventions available for social anxiety, offering beneficial outcomes within a condensed timeframe (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2013).

It is important to note that psychodynamic therapy goes beyond symptom reduction. It focuses on personal growth, self-reflection, and developing a deeper understanding of yourself.

By addressing the underlying causes of social anxiety, it not only provides relief from symptoms but also facilitates long-lasting transformation and a renewed sense of self.

If you’re interested in learning more about psychodynamic therapy and its application to social anxiety, feel free to click here to access our in-depth article. It provides comprehensive insights and valuable information to support your journey of self-discovery and healing.

Just like in any form of psychotherapy, your commitment and active engagement in PDT serve as catalysts for profound transformation and a renewed sense of empowerment in your social interactions.

Interpersonal Therapy (IPT)

Interpersonal therapy is a valuable approach in the treatment of social anxiety, centered around enhancing interpersonal relationships and addressing specific interpersonal difficulties that contribute to social anxiety symptoms.

By focusing on improving communication skills, resolving interpersonal conflicts, and building supportive connections, IPT aims to alleviate social anxiety and enhance overall well-being.

Experts have aptly underscored the significance of securing funding and conducting unbiased examinations of therapeutic approaches that extend beyond the predominant focus on CBT, which often receives substantial funding and research attention (Markowitz et al., 2014).

While interpersonal therapy may not have received as much research scrutiny, it has consistently showcased its effectiveness as a treatment for social anxiety across multiple studies (e.g., Borge et al., 2008; Lipsitz et al., 2008; Stangier et al., 2011).

The extensive body of evidence derived from these studies unequivocally establishes the value of IPT as a credible and advantageous option for individuals seeking relief from social anxiety symptoms.

While cognitive-behavioral therapy appears to yield slightly better results overall, interpersonal therapy serves as a viable alternative for those who may not respond to or feel inclined to try CBT.

At the core of interpersonal therapy lies the recognition that social anxiety often arises from challenges in forming and maintaining healthy relationships.

It acknowledges the impact of interpersonal dynamics on your emotional well-being and self-perception, emphasizing the significance of social interactions in shaping your experience of anxiety.

During IPT, you work closely with a skilled therapist to identify and address specific interpersonal problems that fuel social anxiety.

These difficulties may include struggles in expressing oneself, fear of rejection or judgment, or struggles with assertiveness and setting boundaries.

Through collaborative exploration, IPT helps you develop effective communication skills, assertiveness, and interpersonal problem-solving strategies.

By strengthening your capacity to express emotions, assert needs, and establish healthy boundaries in relationships, you enhance your self-assurance and alleviate the anxiety commonly associated with social interactions.

Additionally, by addressing and releasing suppressed anger and resentment, which are known to contribute to social anxiety symptoms in certain cases (Sulz, 2016), you can experience profound relief and foster greater emotional well-being.

IPT typically consists of structured sessions that focus on specific interpersonal issues. The therapy is often time-limited, ranging from 12 to 16 weeks, with regular sessions scheduled weekly or biweekly.

The time-limited nature of IPT allows for targeted work on interpersonal challenges, promoting efficient progress and positive outcomes.

It’s important to note that IPT is not solely focused on symptom reduction but also on improving overall interpersonal functioning and relationships.

By addressing interpersonal difficulties, you can experience significant relief from social anxiety symptoms, build healthier relationships, cultivate self-assurance, navigate social situations with greater ease, and develop a stronger foundation for meaningful connections.

To learn more about IPT for social anxiety, we recommend you click here to read our in-depth guide.

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT)

Acceptance and Commitment Therapy offers a unique and transformative approach to addressing social anxiety by fostering acceptance, mindfulness, and values-driven action.

In ACT, rather than aiming to eliminate anxiety, the focus is on developing psychological flexibility and learning to live a meaningful life, even in the presence of anxiety.

Due to its roots in traditional CBT, acceptance and commitment therapy has garnered substantial research attention.

A recent meta-analysis of 11 studies confirmed the validity and promising nature of ACT as an effective treatment intervention for social anxiety disorder (Caletti et al., 2022).

However, the authors also underscored the importance of conducting additional studies to examine the long-term effectiveness of ACT in individuals with social anxiety, as the scientific evidence in this area is still scarce.

Through ACT, you learn to observe and accept your anxious thoughts and feelings without judgment, allowing them to come and go without trying to control or avoid them.

This acceptance is combined with the cultivation of mindfulness skills, which enable you to be fully present in the moment and engage with social situations with openness and curiosity.

One of the key concepts in ACT is the identification of personal values – what truly matters to you in life. By clarifying your values, you can align your actions with them, even when anxiety is present.

This values-driven action helps you transcend the limitations of social anxiety and live a rich, meaningful, and authentic life.

ACT also incorporates various experiential exercises and metaphors to facilitate a shift in your relationship with anxiety.

Through practices such as defusion techniques, you learn to create distance from anxious thoughts and see them as passing mental events rather than absolute truths.

This allows you to relate to your anxiety in a more flexible and adaptive way.

ACT is typically delivered in a relatively short-term format, ranging from 8 to 16 sessions. The therapy is highly individualized, tailored to your specific needs and goals.

Regular sessions, often conducted weekly, provide a supportive and collaborative space for you to explore and integrate ACT principles into your life.

By embracing acceptance, developing mindfulness, and aligning your actions with your values, ACT empowers you to move beyond the limitations of social anxiety.

It encourages you to live a more fulfilling and authentic life, grounded in personal values and meaningful connections.

As ACT integrates cognitive-behavioral strategies and mindfulness teachings to help you navigate and embrace uncomfortable thoughts and feelings, you will observe elements from both approaches during therapy.

By the way, if ACT piques your interest, we wholeheartedly recommend the practical Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook by three leading experts on social anxiety, mindfulness, and ACT.

This book (available for purchase here) guides you through their highly effective program, which has shown significant results for treating social anxiety disorder and related shyness.

To learn more about ACT, we recommend you click here to read our in-depth guide to acceptance and commitment therapy for social phobia.

Metacognitive Therapy (MCT)

Metacognitive Therapy offers a unique and innovative approach to treating social anxiety that sets it apart from cognitive behavioral therapy.

While both therapies aim to address cognitive processes, MCT focuses specifically on the regulation and nature of one’s thoughts, providing a distinct perspective.

In contrast, CBT generally concentrates on the content of thoughts and modifying dysfunctional beliefs and behaviors.

The key concept in MCT is metacognition, which involves gaining awareness and understanding of one’s own thinking processes.

Rather than solely examining the content of thoughts, MCT places emphasis on exploring how individuals think and relate to their thoughts (Wells, 2009).

This metacognitive perspective allows individuals to develop insights into their thinking patterns and develop effective strategies to manage and modify these patterns.

By cultivating metacognitive awareness, you can develop a more adaptable and flexible approach to your thinking patterns, leading to liberation from the grip of social anxiety.

MCT distinguishes between two crucial types of thinking processes: positive and negative metacognition.

Positive metacognition encompasses constructive and beneficial thinking patterns, such as problem-solving and self-reflection, which empower you to navigate social situations effectively.

Conversely, negative metacognition involves unhelpful cognitive processes like rumination, worry, and excessive attention to thoughts related to threats.

These negative thought processes are commonly observed among individuals with social anxiety and are believed to perpetuate social anxiety symptoms.

The primary objective of MCT is to identify and modify these negative metacognitive processes that sustain social anxiety.

By accomplishing this, you can transform your relationship with your thoughts and diminish the influence they have on your emotions and behaviors. Ultimately, this paves the way for greater emotional well-being and improved social functioning.

In MCT, you work collaboratively with a therapist to develop metacognitive strategies to challenge and change unhelpful thinking patterns. These strategies may include:

Metacognitive Awareness Training: You learn to recognize and observe your thoughts from a detached perspective, allowing you to gain distance from anxious thinking patterns and reduce their impact.

Cognitive Restructuring: You examine the content of your thoughts and identify any cognitive distortions or biases. Through challenging and reframing these distortions, you can develop more balanced and realistic thinking patterns.

Attention Training: You practice redirecting your attention away from unhelpful thoughts and shifting focus to more positive and adaptive aspects of your experience.

Decentering Techniques: You learn to see your thoughts as passing mental events rather than accurate reflections of reality. This decentering allows you to create space between yourself and your thoughts, reducing their influence on your emotions and behaviors.

MCT is typically administered in a structured format across a specific number of sessions, personalized to address your individual needs and treatment objectives.

The exact duration and frequency of therapy may differ based on your progress and the recommendations of your therapist. However, you can generally anticipate undergoing approximately 8 to 16 sessions.

By transforming your relationship with your thought processes, MCT empowers you to break free from the cycle of negative thinking, enhance metacognitive awareness, and develop a more balanced and adaptive approach to social interactions.

If you’re interested in exploring metacognitive therapy further, you can click here to access our in-depth article on MCT. It provides valuable insights into the principles and practices of MCT in the context of social anxiety treatment.

Mindfulness- & Compassion-Based Therapy

Mindfulness- and compassion-based therapy offers a transformative approach to addressing social anxiety by cultivating inner awareness and fostering compassionate presence.

The practice of mindfulness involves intentionally paying attention to the present moment without judgment.

By cultivating this non-judgmental awareness, you can observe your thoughts, emotions, and bodily sensations related to social anxiety with curiosity and acceptance.

This heightened self-awareness enables you to disengage from automatic patterns of reactivity and cultivate a more skillful and compassionate response, which can lead to a decrease in social anxiety symptoms.

The standard Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) program, developed by Jon Kabat-Zinn (1994), combines mindfulness meditation, gentle movement, and mindful awareness practices to help individuals manage stress, anxiety, and a range of psychological difficulties.

It provides you with practical tools to cultivate mindfulness in everyday life and navigate social situations with greater ease and presence.

MBSR has shown to reduce emotional reactivity and improve emotion regulation in people with social anxiety disorder (Goldin & Gross, 2010).

Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT), originally developed to prevent relapse in individuals with depression, integrates mindfulness practices with elements of cognitive therapy.

It helps you observe and change negative thought patterns that contribute to social anxiety while cultivating a compassionate and non-judgmental stance towards oneself.

MBCT has been found to improve self-esteem and reduce social anxiety symptoms (e.g., Ebrahiminejad et al., 2016).

Another important component of mindfulness-based therapy is the cultivation of self-compassion. Self-compassion involves treating oneself with kindness, understanding, and acceptance, especially during times of struggle or difficulty.

It encourages you to extend the same warmth and compassion towards yourself that you would offer to a dear friend facing similar challenges.

Through self-compassion practices, you develop a nurturing inner voice, fostering self-acceptance and resilience in the face of social anxiety.

Mindful Self-Compassion (MSC), developed by Kristin Neff and Christopher Germer, focuses specifically on fostering self-compassion as a means of healing and growth.

MSC combines mindfulness practices with self-compassion exercises to enhance self-care, build resilience, and develop a more supportive and nurturing relationship with oneself.

Studies have shown that cultivating self-compassion not only effectively alleviates social anxiety symptoms but also acts as a protective quality against the condition (McBride et al., 2022).

These mindfulness- and compassion-based therapies can be pursued as standalone treatments or integrated with other therapeutic approaches.

They offer valuable tools for managing social anxiety symptoms, reducing self-judgment, and cultivating a compassionate and resilient mindset.

Even if you opt for a different therapeutic approach, such as CBT or ACT, it’s worth noting that your therapist may incorporate significant elements of mindfulness- and compassion-based therapy into your treatment journey.

A recent meta-analysis has shown that mindfulness-based interventions hold promise in alleviating symptoms of social anxiety, improving depressive symptoms, mindfulness, quality of life, and self-compassion (Liu et al., 2021).

However, the authors highlight that further research is needed to better understand their efficacy compared to other treatments.

By incorporating mindfulness and compassion into your life, you develop the ability to observe social anxiety with greater clarity and respond to it with kindness and understanding.

These practices foster inner stability, emotional regulation, and a sense of well-being, empowering you to navigate social interactions with increased confidence and authenticity.

If you wish to explore mindfulness meditation, including its effects on the brain and benefits for people with social anxiety, as well as several guided meditations to get you started, we recommend you click here to read our comprehensive introductory guide to meditation.

To experience the advantages of mindfulness and meditation practices, even without engaging in specialized therapies, we strongly recommend that you download the Headspace app.

With its intuitive interface and expert-guided meditations, Headspace provides a seamless platform for fostering mindfulness and self-compassion, supporting individuals with social anxiety on their path to progress.

Multiple studies have provided evidence supporting the positive effects of brief mindfulness interventions using the Headspace app.

These studies have demonstrated significant improvements in irritability, affect, and stress resulting from external pressure (Economides et al., 2018), as well as a significant reduction in anxiety and worry after using Headspace for four weeks (Abbott et al., 2023).

Furthermore, a systematic review, which rigorously considered potential conflicts of interest when assessing the efficacy of mindfulness apps, including Headspace, concluded that the empirical results of trials investigating Headspace are promising (O’Daffer et al., 2022).

By clicking below, you can access a free 7-14 day trial of Headspace and experience how it can support you in integrating mindfulness into your daily routine.

If you are a student, you should click below instead. This will allow you to access a special student discount, tailored to your situation and help you manage social anxiety effectively.

Recall the book we recommended for ACT, the Mindfulness and Acceptance Workbook (available for purchase here).

To learn more about compassion-based therapies for social anxiety, in particular CFT and SMC, you can click here to read our in-depth article.

If you’re genuinely interested in embracing mindfulness, we wholeheartedly endorse this book as an essential companion for your transformative journey. It will help you make the most of your practice, as it focuses on the specifics of social anxiety.

Group Therapy

Group therapy serves as a valuable and enriching approach to addressing social anxiety by providing a supportive and empathetic environment where you can connect with others facing similar challenges.

In a group therapy setting, you have the opportunity to share experiences, gain insights, and learn valuable skills from both the therapist and fellow group members.

The power of group therapy lies in its ability to offer a sense of belonging and validation.

Through interacting with others who understand the complexities of social anxiety, you can gain a renewed perspective on your own struggles and realize that you are not alone in your journey.

In a group therapy setting, you can explore social interactions, practice new skills, and receive feedback in a safe and non-judgmental space.

By observing and participating in group dynamics, you can gain valuable insights into your own thoughts, emotions, and behaviors related to social anxiety.

This increased self-awareness can lead to transformative personal growth and a greater understanding of the underlying patterns that contribute to social anxiety.

Group therapy typically consists of a small group of individuals, facilitated by one or more trained therapists who specialize in social anxiety.

The duration and frequency of sessions can vary, with sessions typically held weekly or biweekly. The length of group therapy can range from a few weeks to several months, depending on the specific program and individual needs.

In a group therapy setting, you will engage in various therapeutic activities, such as structured discussions, role-playing exercises, and social skills training.

These activities are designed to enhance self-confidence, improve communication skills, challenge negative beliefs, and develop effective coping strategies for social anxiety.

The benefits of group therapy extend beyond the therapy room. Through the connections formed with group members, you can establish a network of support and encouragement, providing ongoing support and motivation in your social anxiety recovery journey.

The shared experiences and perspectives offered by group members can offer a unique source of insight and encouragement, fostering personal growth and empowerment.

A meta-analysis including 36 randomized-controlled trials found group therapy for social anxiety to be as effective as individual psychotherapy or pharmacotherapy (Barkowski et al., 2016).

However, it’s important to note that group therapy may not be suitable for everyone, and individual preferences and needs vary. Some individuals may prefer the one-on-one interaction of individual therapy, while others find the dynamic of group therapy particularly beneficial.

Group therapy and individual therapy can be pursued as separate treatment options or combined to create a comprehensive and tailored approach to addressing social anxiety.

If you are interested in exploring group therapy as a treatment option for social anxiety, reach out to mental health professionals, community centers, or local therapy groups to inquire about available group therapy programs in your area.

Remember, you don’t have to navigate your journey to recovery alone. Group therapy offers a unique and supportive space where you can find solace, connection, and growth with others who share similar experiences.

To learn more about group therapy for social anxiety, we recommend you click here to read our in-depth guide.

C. Medication: Strengthening Your Treatment Journey

When seeking to manage social anxiety, medication can be a valuable adjunct to psychotherapy.

It’s important to note that medication is not a standalone solution but rather a complementary treatment component that can enhance the effectiveness of therapy.

If you are considering medication as part of your treatment plan, it is essential to discuss it with your therapist and consult with a healthcare professional, such as a doctor or psychiatrist.

They will guide you through the process, explore different options, and prescribe medication tailored to your specific needs.

Regular monitoring, check-ins, and potential adjustments under their supervision contribute to your overall safety and well-being.

Collaborating with a qualified healthcare professional ensures that medication is utilized in a responsible and informed manner, supporting your journey toward managing social anxiety.

It’s understandable that many people may have reservations or concerns about taking medication. This is a personal decision, and it’s important to respect your own preferences and comfort level.

However, it’s also crucial to be well-informed about the potential benefits that medication can offer.

For some individuals, medication can significantly reduce symptoms and provide relief from the distress caused by social anxiety. It can help regulate brain chemistry, manage anxiety symptoms, and support overall well-being.

Let’s take a closer look at the various types of medications commonly prescribed to treat social anxiety disorder.

Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs)

SSRIs, including fluoxetine (Prozac), sertraline (Zoloft), and escitalopram (Lexapro), are commonly prescribed medications for social anxiety.

By increasing serotonin availability in the brain, SSRIs help regulate mood and reduce anxiety symptoms.

They are considered a first-line treatment for social anxiety, as they have demonstrated effectiveness in reducing anxiety, improving social functioning, and enhancing overall well-being (Melaragno, 2021).

It is important to note that SSRIs may take several weeks to reach their full effectiveness, and any side effects are usually mild and temporary.

For a comprehensive understanding of SSRIs for social anxiety, you can click here to read our in-depth article discussing their benefits, side effects, and the scientific evidence of their effectiveness.

Regular monitoring by a healthcare professional is required when taking SSRIs.

Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs)

SNRIs, such as venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta), are another class of medications commonly prescribed for social anxiety.

SNRIs work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain, similar to SSRIs, but they also target norepinephrine, another neurotransmitter involved in mood and anxiety regulation.

SNRIs can be particularly beneficial for individuals experiencing both social anxiety and depression symptoms (Mitsui et al., 2022).

Like SSRIs, SNRIs may take several weeks to produce noticeable effects, and side effects are generally manageable.

For a comprehensive understanding of SNRIs for social anxiety, you can click here to read our in-depth article discussing their benefits, side effects, and the scientific evidence of their effectiveness.

Regular monitoring by a healthcare professional is required when taking SNRIs.

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepines, such as diazepam (Valium) and alprazolam (Xanax), are fast-acting medications that provide temporary relief from anxiety symptoms.

They work by enhancing the calming effects of a neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) in the brain.

Benzodiazepines are typically prescribed for short-term use or as-needed basis due to their potential for dependence and withdrawal symptoms with long-term use (Hindmarch, 2009).

They can be useful in situations requiring immediate anxiety reduction, such as specific social events.

However, their long-term use for social anxiety is generally avoided unless other treatment options have been ineffective.

For more information regarding the short-term benefits, risks, and side effects of benzodiazepines for social anxiety, you can click here to read our comprehensive article on the topic.

Close monitoring by a healthcare professional is required when taking benzodiazepines.

Beta-Blockers

Beta-blockers, such as propranolol, are medications primarily used to manage heart conditions.

However, they are also prescribed off-label for social anxiety to help reduce physical symptoms associated with anxiety, such as rapid heartbeat, trembling, and sweating.

Beta-blockers work by blocking the effects of adrenaline on the body, thereby reducing the physical manifestations of anxiety (Elsey et al., 2020).

They are typically taken on an as-needed basis before anxiety-provoking situations, such as public speaking or performances.

To learn more about the use of beta-blockers to manage the physical symptoms of social anxiety, you can click here to read our in-depth article.

Regular monitoring by a healthcare professional is required when taking beta blockers.

Less Utilized Options: MAOIs and RIMAs

While the previously mentioned medications are frequently prescribed for social anxiety disorder, it’s essential to mention two less common alternatives that may be considered in specific cases: MAOIs and RIMAs.

While these options may not be as commonly prescribed due to potential side effects and interactions, they can offer relief for individuals with social anxiety disorder when other medications have proven ineffective.

MAOIs (Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors)

MAOIs, or Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors, are a class of medications that can be considered for the treatment of social anxiety disorder when other options have been ineffective.

They work by inhibiting the enzyme monoamine oxidase, which is responsible for breaking down neurotransmitters such as serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine in the brain.

By inhibiting this enzyme, MAOIs increase the availability of these neurotransmitters, leading to improved mood and reduced anxiety symptoms. Some commonly prescribed MAOIs include phenelzine (Nardil), tranylcypromine (Parnate), and isocarboxazid (Marplan).

It’s important to note that MAOIs are not as commonly prescribed today due to several factors. One reason is the potential for serious side effects and interactions (Thase, 2012).

MAOIs have been associated with hypertensive crises, a dangerous increase in blood pressure, when consumed along with certain foods and beverages that contain high levels of tyramine. These include aged cheeses, cured meats, and fermented products.

Additionally, MAOIs can interact with various medications, including certain antidepressants, cold and cough medications, and decongestants. These interactions can lead to severe adverse effects.

Therefore, if you are prescribed an MAOI, it’s crucial to inform your healthcare provider about all the medications you are taking to avoid potential complications.

Due to their dietary restrictions and interactions, MAOIs are typically reserved for cases where other treatment options have been exhausted or in situations where their benefits outweigh the risks (Thase, 2012).

For a comprehensive understanding of MAOIs for social anxiety, you can click here to read our in-depth article discussing their benefits, evidence of their effectiveness, as well as their considerable risks and side effects.

As with all medications discussed here, close monitoring and supervision by a healthcare professional is required when taking MAOIs.

RIMAs (Reversible Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase A)

RIMAs, or Reversible Inhibitors of Monoamine Oxidase A, are a newer class of medications that target the enzyme monoamine oxidase, similar to MAOIs.

However, RIMAs differ in that they are considered reversible inhibitors, meaning their effects on the enzyme are temporary.

Moclobemide is an example of a RIMA that has been used in the treatment of social anxiety disorder. It selectively inhibits monoamine oxidase-A, the subtype primarily responsible for breaking down serotonin and norepinephrine in the brain.

By temporarily inhibiting this enzyme, RIMAs increase the levels of these neurotransmitters, leading to a reduction in anxiety symptoms (Williams et al., 2017). Compared to traditional MAOIs, RIMAs generally have a more favorable side effect profile.

However, it’s important to note that RIMAs can still cause side effects such as dizziness, insomnia, and gastrointestinal disturbances.

As with any medication, it’s essential to discuss the potential benefits and risks with your healthcare provider to determine if a RIMA is a suitable option for your specific case of social anxiety disorder.

While RIMAs offer certain advantages over traditional MAOIs, they are not typically considered as first-line treatments. Their use may be reserved for cases where other treatment options have been exhausted or when their benefits outweigh potential risks.

For a comprehensive understanding of RIMAs for social anxiety, you can click here to read our in-depth article discussing their benefits, effectiveness, as well as their risks and potential side effects.

Close monitoring by a healthcare professional is still necessary when using RIMAs.

A Natural Alternative: CBD (Cannabidiol)

In recent years, CBD has gained attention as a potential natural alternative for managing social anxiety.

CBD is a non-intoxicating compound derived from the cannabis plant. It is known for its potential therapeutic effects, including anti-anxiety properties.

CBD interacts with the body’s endocannabinoid system, which plays a role in regulating mood, anxiety, and stress responses. Some studies suggest that CBD may help reduce anxiety symptoms, promote relaxation, and improve sleep quality.

While CBD may offer calming effects and is available without a prescription in many states and countries, it is advisable to consult with a healthcare professional before incorporating it into your treatment plan.

They can provide guidance on appropriate dosages, potential interactions with other medications, and monitor your progress.

While research on CBD for social anxiety is ongoing, a recent literature review concluded that CBD can effectively reduce social anxiety without causing sedation or cognitive side effects (Fliegel & Lichenstein, 2022).

After extensive research, we have carefully selected a specific CBD oil that we recommend to people with social anxiety who are considering CBD products for symptom reduction.

It is entirely non-psychoactive, meaning it does not produce any “high” effects whatsoever. Rest assured, this CBD oil is well within the legal limits, making it a safe and compliant choice for anyone seeking natural support for their social anxiety.

Moreover, we have received positive feedback from socially anxious individuals who have tried this product, further confirming its potential to alleviate social anxiety symptoms.

However, it’s crucial to emphasize that while CBD can be beneficial for many, individual reactions may vary. Therefore, we strongly recommend consulting with your healthcare professional before incorporating CBD into your routine.

If you’re interested in exploring the benefits of CBD for managing social anxiety, we invite you to check out our selected CBD oil. To ensure quick and efficient delivery, we advise choosing the online store that is geographically closest to your location.

Our Top Pick: Poland

Our Top Pick: Germany

Our Top Pick: Finland

Our Top Pick: Denmark

Our Top Pick: Spain

Our Top Pick: Sweden

Our Top Pick: Italy

Our Top Pick: France

Our Top Pick: Netherlands

Our Top Pick: Portugal

Before you start using CBD to address your social anxiety, it’s essential to have a conversation with your doctor. They can provide valuable guidance based on your individual circumstances.

Additionally, it’s important to be aware of and follow the local laws and regulations pertaining to CBD usage and to strictly adhere to the dosage instructions provided by the manufacturer.

For a comprehensive guide on CBD for social anxiety, including an in-depth examination of the scientific evidence supporting its effectiveness in reducing symptoms, you can click here to access our comprehensive guide.

Remember, medication should always be prescribed and monitored by a qualified healthcare professional who will consider your individual needs, medical history, and potential interactions with other medications.

They will guide you through the process, monitor your progress, and make any necessary adjustments to ensure the best outcomes for your social anxiety treatment.

If you are interested in learning more about medication for social anxiety, we recommend clicking here to access our in-depth guide. It covers all the different types of medication commonly prescribed for social anxiety, providing detailed information on their benefits, effectiveness, potential side effects, associated risks, and specific considerations to keep in mind.

Recommended Online Psychiatry Service

You can conveniently schedule an online appointment with a qualified psychiatrist, licensed in your state, through our following partner-link, which also offers a special discount code.

The psychiatrists from Talkspace can provide a comprehensive evaluation, offer a diagnosis if applicable, and prescribe medication, such as those discussed above, if deemed appropriate for your specific needs.

Your prescription will be sent to a local pharmacy of your choice. Every three months you’ll have a follow-up video appointment, and you can message your provider any time.

Prescription treatment with Talkspace costs you about $30/month if you are insured, and about $60-$100/month when you pay out-of-pocket. Remember, through our link you will get a special coupon code.

D. Self-Help Techniques & Lifestyle Changes: Taking Control

Beyond therapy and medication, self-help techniques and lifestyle changes play a pivotal role in managing social anxiety (Lewis, Pearce, & Bisson, 2012).

These strategies empower you to take an active role in your treatment, promoting overall well-being and enhancing your ability to cope with social anxiety symptoms effectively.

In this section, we will explore a range of self-help techniques and lifestyle changes that can complement professional treatment.

By incorporating these approaches into your daily life, you can further support your journey towards managing social anxiety and regaining confidence in social situations.

First and foremost, let’s lay the groundwork by establishing a solid foundation for well-being. This means emphasizing the importance of good sleep, regular physical activity, and a healthy diet to nurture your overall health and mental well-being.

Next, we will delve into building self-awareness, a crucial aspect of managing social anxiety. Through mindfulness meditation, journaling, and identifying triggers, you will gain a deeper understanding of yourself and your emotions.

Acquiring coping strategies will be another significant aspect of your journey. We will explore techniques such as deep breathing, directing attention to non-threatening stimuli, challenging negative thoughts, practicing positive self-talk, and embracing gradual exposure.

Additionally, we will prioritize the improvement of social skills as a means of overcoming social anxiety challenges. Identifying your weaknesses, setting achievable goals, seeking learning resources, regular practice, and engaging in self-reflection will be integral parts of this process.

Remember, finding the right combination of strategies that resonate with you is essential, and it may take time to discover what works best for your unique needs.

Establishing a Foundation for Well-being

To effectively manage social anxiety, it is crucial to establish a solid foundation for overall well-being. This involves adopting healthy habits and making lifestyle changes that support your mental and physical health.

By prioritizing these foundational elements, you can enhance your resilience and ability to cope with social anxiety. Here are three key areas to focus on:

Good, Sufficient Sleep

Adequate sleep is fundamental for managing anxiety and maintaining emotional well-being.

Lack of sleep has been linked to increased social anxiety symptoms, stress and difficulty in social situations (Stein, Kroft, & Walker, 1993).

Establish a consistent sleep routine, create a calm sleep environment, and practice good sleep hygiene habits such as avoiding stimulants before bedtime and limiting screen time.

Here are a few general guidelines for improved sleep:

- Establish a consistent sleep schedule, even on weekends.

- Establish a calming bedtime routine to signal your body it’s time to unwind. Consider using lavender aroma (available for purchase here) to promote sleepiness and enhance sleep quality.

- For sleep problems, melatonin is a good option (available for purchase here). It is a dietary supplement and is not sedating. Before use, it is best to consult a doctor for the correct dosage.

- Ensure your sleep environment is comfortable, quiet, and dark.

- Reduce screen time before bed to minimize exposure to blue light, which negatively affects sleep quality. Consider using blue light blocking glasses (available for purchase here).

- Avoid heavy meals, caffeine, and alcohol close to bedtime.

Prioritize sleep as an essential component of your self-care routine, as it plays a crucial role in improving emotional well-being and reducing anxiety.

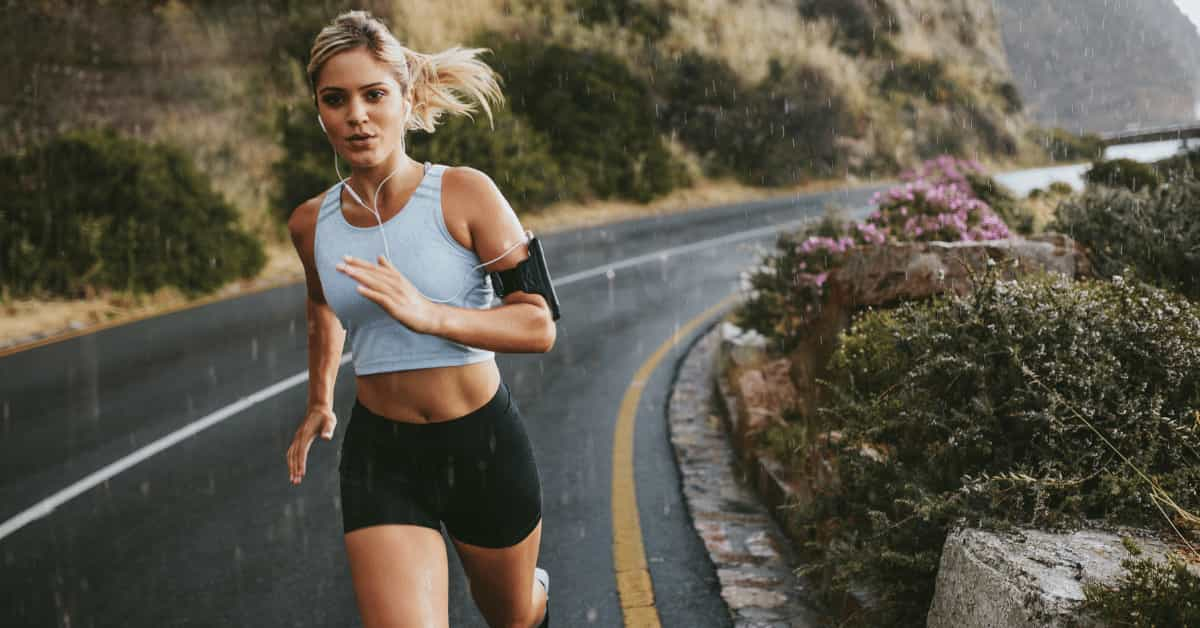

Regular Physical Activity

Engaging in regular physical activity is a powerful tool for managing social anxiety. Exercise helps reduce stress, boost mood, and increase overall well-being.

It has been found to be an especially useful intervention for individuals with high levels of anxiety (Lucibello, Parker, & Heisz, 2019).

Find physical activities that you enjoy, whether it’s going for a walk, practicing yoga, swimming, or engaging in team sports.

Aim for at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise most days of the week.

Incorporating physical activity into your routine can provide a natural outlet for stress, promote relaxation, and boost your self-confidence.

Healthy Diet

The food we consume has a significant impact on our mental well-being. It has been found that healthy diets can effectively reduce anxiety and depressive symptoms (Kiecolt-Glaser, Jaremka, & Hughes, 2014).

Adopting a healthy diet can positively influence mood, energy levels, and overall functioning. Incorporate nutrient-rich foods such as fruits, vegetables, whole grains, lean proteins, and healthy fats into your meals.

Reduce or avoid excessive consumption of processed foods, sugary snacks, and caffeinated beverages, as they can contribute to feelings of anxiety and stress.

Extra: Dietary Supplements for Anxiety Reduction

We’ve gathered key findings from several studies exploring dietary supplements for anxiety reduction.

We would like to clarify that we are not endorsing the specific products mentioned in this supplements section. Our intention is solely to present preliminary scientific findings related to these supplements and highlight those that have shown promise as anxiolytic (anxiety-reducing) agents.

Always exercise caution and consult with a healthcare professional before considering the use of any dietary supplements.

It is essential to keep in mind that the preliminary findings presented here require further research to establish their validity conclusively.

Study 1 (Lane, 2014): Supplement Combination

- Supplements Tested: GABA, L-theanine, Passiflora incarnata (purchasable here), Prunus cerasus.

- Effects: Significant improvement in anxiety symptoms compared to placebo, no reported side effects.

Study 2 (Fadaki et al., 2017): Ginger Extract

- Effects: Ginger extract (purchasable here) effectively reduced anxiety levels in mice, showing promise as a natural alternative to medication.

Study 3 (Weeks, 2009): Anxiolytic Properties Review

- Supplements Studied: Kava (purchasable here), passion flower (purchasable here), skullcap (purchasable here), hops, lemon balm (purchasable here), Valerian root (purchasable here), Magnolia, Phellondendron bark extracts, GABA, theanine, tryptophan, 5-HTP.

- Findings: These supplements exhibit anxiolytic effects or mild relaxation properties, but more research is needed for medicinal value.

Study 4 (Etaee et al., 2019): Cinnamaldehyde (Cin)

- Effects: Mice treated with Cin (purchasable here) showed increased exploration and time spent in open areas, suggesting anxiolytic effects.

Study 5 (Akhgarjand et al., 2022): Ashwagandha Supplementation

- Effects: A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating the effect of Ashwagandha (purchasable here) extract on anxiety and stress revealed significant reductions in anxiety and stress levels.

- The authors point out that further research is necessary to establish the clinical efficacy of Ashwagandha as a treatment for anxiety and stress.

Furthermore, several other supplements known as neutraceuticals have gained popularity in recent years for their positive effects on mental health. Some of the most common neutraceuticals include:

Sacha Inchi Oil (available for purchase here):

Sacha Inchi oil is a rich source of omega-3 fatty acids, particularly alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). Omega-3 fatty acids are known for their beneficial effects on brain health and mood regulation. They play a crucial role in supporting cognitive function, reducing inflammation in the brain, and may help alleviate symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Rhodiola Rosea (available for purchase here):

Rhodiola Rosea is another adaptogenic herb with potential benefits for mental health. It is believed to enhance the body’s resilience to stress and fatigue, leading to improved cognitive function and reduced feelings of burnout. Rhodiola may also support mood balance and may be helpful in managing symptoms of mild to moderate depression.

Ginkgo Biloba (available for purchase here):

Ginkgo Biloba is derived from the leaves of the Ginkgo tree and has been used in traditional medicine for centuries. It is known for its potential to enhance cognitive function, including memory and concentration. Some research suggests that Ginkgo Biloba may improve blood flow to the brain, providing neuroprotective effects and supporting overall mental clarity.

By focusing on good, sufficient sleep, incorporating regular physical activity into your lifestyle, and maintaining a healthy diet, you lay a strong foundation for managing social anxiety.

These lifestyle changes support your overall well-being and provide a solid base for implementing additional self-help techniques.

Remember, building these habits takes time, so be patient with yourself and celebrate each small step towards improved well-being.

Building Self-Awareness

Developing self-awareness is an essential aspect of managing social anxiety.

It involves gaining insight into your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors, which can help you identify triggers and patterns associated with social anxiety.

By building self-awareness, you can cultivate a deeper understanding of yourself and make informed choices for managing social anxiety effectively. Here are three techniques to assist you in this process:

Mindfulness Meditation

Mindfulness meditation is a practice that involves paying non-judgmental attention to the present moment. It can help you become more aware of your thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations related to social anxiety.

Regular mindfulness meditation sessions can create a sense of calm, increase self-compassion, and reduce reactivity to anxiety triggers. Consider incorporating guided mindfulness meditations or mindfulness-based apps into your daily routine to enhance self-awareness.

Mindfulness, including when practiced as a self-help technique, has been shown to be an effective intervention for social anxiety, leading to reduced symptoms (Kocovski et al., 2019).

We highly recommend using Headspace as a valuable resource for individuals with social anxiety, who we have partnered with to further support your journey.

Headspace offers a wide range of professionally guided meditations specifically designed to support mental well-being, including practices that can help you grow accustomed to mindfulness meditation, make it a habit, and experience its numerous benefits.

By clicking the button below, you can access a free trial of the app and explore its extensive library of guided meditations.

If you are a student, you should click below instead. This will allow you to access a special student discount, tailored to support your well-being and help you manage social anxiety effectively.

If you are the type of person who experiences discomfort or pain during meditation, you should use a two-piece meditation cushion (available for purchase here). This cushion elevates your hips and provides comfortable foot support, allowing for longer and more pleasant meditation sessions.

For a more comprehensive exploration of mindfulness and meditation for social anxiety, we invite you to click here and delve into our detailed guide.

This comprehensive resource provides valuable insights into the science behind mindfulness meditation, its numerous benefits for managing social anxiety, and practical guidelines on how to incorporate mindfulness practices into your daily life.

Journaling

Journaling provides a private space for self-reflection and expression and has been linked to increased self-efficacy (Fritson, 2008), an essential psychological trait that significantly influences whether individuals can effectively overcome social anxiety.

By writing down your thoughts, feelings, and experiences related to social anxiety, you can gain insights into your triggers, fears, and patterns of thinking.

Use your journal to explore your emotions, reflect on challenging situations, and track your progress over time.

Consider using prompts like “How did social anxiety affect me today?” or “What fears and beliefs are associated with my social anxiety?” to guide your journaling practice.

“What steps have I taken to confront my social anxiety?” or “What strategies have I used to cope with social anxiety, and how effective were they?”

“Journal Therapy for Calming Anxiety” offers a year-long journey of self-discovery and healing through therapeutic writing prompts (available for purchase here).

Authored by Kathleen Adams, a seasoned clinical professional, this journal provides a structured approach to managing anxiety.

We highly recommend this resource to individuals seeking to navigate their social anxiety journey with the support of therapeutic journaling techniques.

Identifying Triggers

Identifying triggers is a crucial step in managing social anxiety. Triggers are situations, events, or thoughts that elicit anxiety or distress.

Take time to reflect on past experiences and identify specific situations or thoughts that consistently evoke anxiety.

Common triggers may include public speaking, meeting new people, or situations involving scrutiny or judgment.

By becoming aware of your triggers, you can develop strategies to manage them effectively and prepare yourself mentally and emotionally.

By practicing mindfulness meditation, journaling, and identifying triggers, you can develop a deeper level of self-awareness.

These techniques allow you to observe and understand your social anxiety on a more profound level, empowering you to make conscious choices in how you respond to anxiety-provoking situations.

Acquiring Coping Strategies

Developing effective coping strategies is essential for managing social anxiety.

These strategies can help you navigate anxiety-provoking situations, challenge negative thoughts, and cultivate a more positive mindset.

By incorporating these coping strategies into your daily life, you can build resilience and enhance your ability to cope with social anxiety. Here are several techniques to consider:

Deep Breathing

Deep breathing exercises are simple yet powerful tools for managing anxiety.

Practice diaphragmatic breathing by inhaling deeply through your nose, allowing your belly to expand, and exhaling slowly through your mouth. Repeat this process several times, focusing on the rhythm of your breath.

This technique activates the body’s relaxation response, reducing anxiety and promoting calmness. It also helps alleviate physical tension, particularly among individuals with high anxiety sensitivity (Khng, 2017), a common trait in people with social anxiety.

Incorporating deep breathing regularly into your routine can be an effective way to manage social anxiety and experience a greater sense of tranquility.

Directing Attention to Not-Threatening Stimuli

Enhancing attentional control and purposefully directing focus towards non-threatening stimuli in social situations has demonstrated great promise as an effective tool for individuals struggling with social anxiety (Fistikçi et al., 2015).

As a result, this approach is progressively being integrated into treatment protocols.

When anxious, engage your senses by focusing on your surroundings, observing details, or engaging in activities that capture your attention.

This shift in focus helps break the cycle of anxious rumination and promotes a sense of grounding.

By the way, one of the most powerful tools to train your attention is through regular meditation and mindfulness practice. You can click here to download our recommended meditation app for those with social anxiety.

Challenging Negative Thoughts

Social anxiety is frequently accompanied by negative self-perceptions and distorted thinking, which can exacerbate the condition (Dodge et al., 1988).

To tackle these negative thoughts, it is essential to assess their validity and substitute them with more realistic and compassionate perspectives.

Engage in the practice of reframing your thoughts by asking yourself probing questions and exploring alternative interpretations of social situations.

For example: “Everyone at the party will think I’m boring and won’t like me.“

Ask yourself: “What evidence do I have to support this belief that everyone will find me boring?” and “Are there any past experiences where people have enjoyed my company or found me interesting?“

Consider other possible explanations for people’s behaviors or reactions: “Maybe some people at the party will find me interesting, and others may not, and that’s normal for social situations.“

Then, create a more balanced and compassionate thought: “I can’t control everyone’s opinions, but I can be myself and focus on connecting with those who appreciate and enjoy my company.“

Practicing Positive Self-Talk

Positive self-talk is a powerful tool that can help you counter self-doubt and negative self-judgment, fostering a more supportive and encouraging mindset.

Numerous studies, such as the research conducted by Shi et al. (2017), have shown that engaging in self-reinforcing, positive self-talk can act as a protective factor against anxiety, including social anxiety.

Take a moment each day to remind yourself of your strengths and past successes. Celebrate your achievements, no matter how small they may seem. By doing so, you can reinforce positive beliefs about your capabilities and build a stronger sense of self-worth.